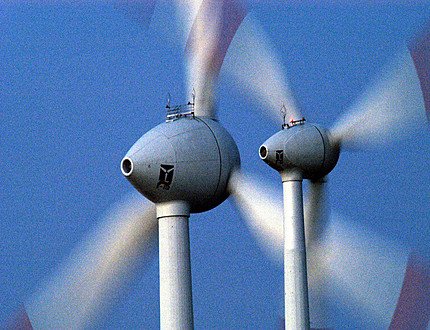

Vestas chief says wind power industry is showing signs of recovery, and blames nimbyism for blocking projects in Britain

Vestas, the wind turbine manufacturer that laid off 425 workers when it closed its Isle of Wight factory this month, has hired more than 5,000 extra workers for its new factories in China, the US and Spain. .

The company said it was expanding heavily in China and the US because these markets were growing the fastest, in contrast to the sluggish pace of wind farm development in the UK.

Vestas wants to supply all its markets from domestic factories, which is why the company decided to stop making turbines to export to the US from its Isle of Wight factory.

Announcing a 15% fall in quarterly profits today, the chief executive, Ditlev Engel, defended the decision: “We are moving to the US because it makes sense to be close to where the action is.”“We are moving to the US because it makes sense to be close to where the action is.”

The company had planned to convert the Isle of Wight factory so that it made turbines for the UK market, because it expected that government renewable energy policies would lead to a big increase in the number of wind farms being built here. “But it just didn’t happen,” he said.

The UK wind market is still relatively small. Last year, about 0.5GW of wind farms were installed in the UK, compared with 8.5GW in the US, the world’s largest producer of wind energy. Because of the transport costs of shipping turbines large distances, it makes sense for factories to be located close to where they will be deployed. The cost of transporting blades from the Isle of Wight to the US was higher than the labour costs needed to make them, for example.

Vestas is also heavily expanding into China, which is the world’s fourth largest wind energy producer but is forecast to overtake the US soon. In China, the government requires that at least 80% of all wind farms are made using domestically manufactured components, requiring Vestas to open new factories there if it wants a big slice of the market. The vast majority of the new 5,000 jobs are in China and the US.

Engel again hit out at nimbys and local politicians for blocking onshore projects, which he said had stymied growth in the UK market. As a result, Ditlev said that not enough wind farms were being built in the UK to support a factory in the country.

“It’s very important to recognise that if the green agenda is going to move ahead the issue of planning has to be addressed,” he said. “To get to the 2020 [renewable energy] targets things have to move pretty fast. You have to accept changes. That means people have to engage, not just say we don’t want it [a wind farm] here.”

The Guardian has also obtained a letter from the Conservative MP for the Isle of Wight, Andrew Turner, calling on the local council to block an application to erect six turbines near the village of Wellow on the island in 2006 because of the impact on the countryside. Vestas executives in the UK had warned the council at the time that if the project was rejected, it could lead to the eventual closure of the factory because it would undermine the UK’s commitment to wind energy.

“I fully understand that as a country we need to reduce our carbon footprint and welcome other initiatives,” he wrote, “[but] I do not accept that a convincing case has been made that the development will be economically beneficial to the Island.” The project was rejected and no onshore wind farms have yet been built on the Isle of Wight.

Vestas also said that the wind power industry was showing signs of recovery after being paralysed by the effects of the credit crunch. Engel said that banks had begun lending to wind farm developers again and that the firm had seen an increase in orders in the past month.

The company said government financial stimulus measures designed to kick-start such infrastructure projects were starting to have an effect. New banks were also prepared to lend to projects, Vestas said, but it added that the more thorough due diligence they were insisting on meant it took longer to secure financing than before the credit crunch.

The economic downturn also contributed to the decision to close the Isle of Wight factory. This was partly because it slowed the development of wind farms here even more, but also because the lower global demand meant the factory was not needed to make turbines for other markets and Vestas was left with an excess of manufacturing capacity in northern Europe. Vestas also shut factories in Denmark, with the loss of 1,142 jobs.

Vestas reported that pre-tax profits for the three months to the end of the June were down by 15% to €78m (£67m), in large part because of redundancy payments it made to the workers it laid off, and to pay salaries for an enlarged workforce elsewhere.