Using pipe networks to pump heat into homes and businesses has long been popular in Continental Europe. But it is only now getting a serious look in Britain as a way to raise energy efficiency and make more use of renewable fuels for heating.

Such systems can use waste heat, produced as a byproduct of electricity generation or other industrial processes, to warm homes and businesses, replacing on-site boilers. With this approach, known as combined heat and power, or cogeneration, plants generate hot water that is circulated to surrounding neighborhoods, rather than expelling heat through cooling towers.

“You’re actually using the heat that would otherwise be thrown away,” said Michael King, an associate at the Combined Heat and Power Association, a trade group.

Such savings are crucial if Britain is to meet its legally binding target of cutting carbon emissions 80 percent by 2050, Lord Philip Hunt, a minister in the Department of Energy and Climate Change, said during an interview.

“We are serious” about district heating, which could eventually supply as many as eight million British households, meeting about 14 percent of the country’s heat demand, up from less than 2 percent now, he said.

While it lacks the eye-catching character of other green technologies like wind turbines, district heating offers big potential advantages. Once the pipes are in place, they can distribute heat generated by any number of sources, meaning they will be adaptable as new low-carbon fuels emerge.

“We’ve got new gas grids going in, but there are question marks over how long that gas supply will be available,” said Nick Rau, an energy campaigner at Friends of the Earth. “We could replace that with a district heating network, and then the energy could be supplied by whatever fuel is available.”

Heat networks already allow for more use of renewable fuels like biomass, or plant materials used as fuel, which is often impractical on a small scale but can be burned in large facilities to create heat that is piped into homes.

The technology has come a long way since the Romans outfitted buildings with ducts for hot air, more than 2,000 years ago; and even since the New York Steam Co. began pumping steam under the streets of Manhattan in 1882.

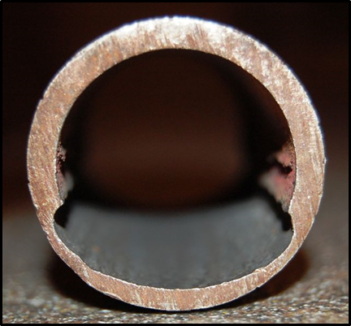

Piped heat systems are now built from super-efficient insulating materials rather than relying on easily damaged external insulation, and they carry hot water rather than high-pressure steam, making them less likely to leak.

Modern district heating networks in Denmark supply 60 percent of heating, much of it from combined heat and power plants. In Austria, district heating provides 36 percent of the heat for the capital, Vienna. Germany, Finland, Iceland and Sweden are also big district heat users — as is Russia, although its systems are mostly dilapidated and woefully inefficient.

In the United States, aging steam systems are in use in cities including New York, Philadelphia and Detroit, and in some large hospitals and universities. But $1.5 billion intended mainly to finance new district heating programs was dropped from the February economic stimulus package put together by the administration of President Barack Obama during last-minute congressional negotiations, said Mark Spurr, the legislative director in Minneapolis for the International District Energy Association, a nonprofit trade association based in Westborough, Massachusetts.

Britain has had a mixed history with district heating, which was installed in some public housing projects in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. Pipes were poorly insulated, and residents had little control over the temperature, Mr. King said. “The only way they could control the heat was by opening the window.”

Now, though, with its tough carbon-cutting target looming, and a commitment to get 15 percent of all energy from renewable sources by 2020, Britain is putting district heating and combined heat and power back on the front burner.

The government allocated £25 million, or $40 million, for district heating in April in its annual budget. In a consultation on heat and energy-saving published in February, the Department of Environment and Climate Change proposed rewriting regulations to aid the installation of district heating and working with local authorities to bring the systems into wider use.

The biggest obstacle is money. While the heat they distribute may be inexpensive, the cost of installing pipe networks is high, and the work can be disruptive.

The systems have been most successful in places where government has gotten involved, with planning, incentives and regulation if not direct financial support, said Robin Wiltshire, technical director of the Building Research Establishment, a construction consulting body, and chairman of the district heating and cooling research group at the International Energy Agency in Paris.

Lord Hunt, of the climate change department, said British officials were willing to shoulder some of the burden, and hoped to work in partnership with private energy companies. “I think you’ll have a sort of mixed approach to this,” with the private sector and government working in tandem, he said.

Some projects are already under way.

The London Development Agency is planning a 67-kilometer, or 42-mile, pipe network to transport waste heat from Barking Power Station, in the eastern suburbs, to as many as 120,000 homes in the city by late next year or early 2011.

In Southampton, on the south coast, a district heating network is pumping heat from a geothermal well, along with heat created by electricity generation. Developed by the city and Utilicom, an energy company specializing in district heating, the network is being expanded this year with the aid of more than £3 million from the government.

Nottingham and Birmingham are two other cities that are expanding recently installed systems.

Getting new systems going is a big undertaking. Alastair D. McMahon, a senior consultant at the environmental group BioRegional, said problems, including high pipe prices caused by a shortage of producers, would take time to solve.

Still, even slow progress would bring meaningful carbon savings, said Mr. King, of the heat and power trade group.

Mr. Wiltshire, of the Building Research Establishment, said: “I don’t think we should ignore any of these technologies. You’ve just got to go for this, for district heating, in order that you can start to really convincingly use heat that’s just being thrown away at the moment.”